LUCY GORDON

Answering the Call of an Insatiable Beast

2024

❦

Katie Paine & Samuel Murnane, CurrentsGallery Two, 17 Aug 2024—15 Sept 2024

In Currents, Katie Paine and Samuel Murnane’s recent exhibition at TCB Gallery, the Kraken emerges as a beast of paradox—a symbol of the drama of alienation functioning as the colossal communicator. With tentacles of copper, aluminium, steel, and polyethylene nestled along the ocean floor, its solitary, deep-sea existence fulfills the fast-paced whims of those of us on land.

The very etymology of the word Kraken comes from the Old Norse verb at kraka, meaning "to drag downward."[1] Intrinsic to the Kraken’s being is the desire to forge itself with another entity, consume it, pull it to the ocean depths, and make one with its prey. The psychoanalytic theories of Otto Rank and Sigmund Freud, specifically their concept of ‘the birth trauma,’ suggest that this allure of unification—the return to some primordial womb—is innate to all entities.[2] The Kraken’s calls to land are an attempt to transcend beyond the ego towards an “oceanic feeling:” a utopian oblivion wherein the birth trauma has resolved.[3]

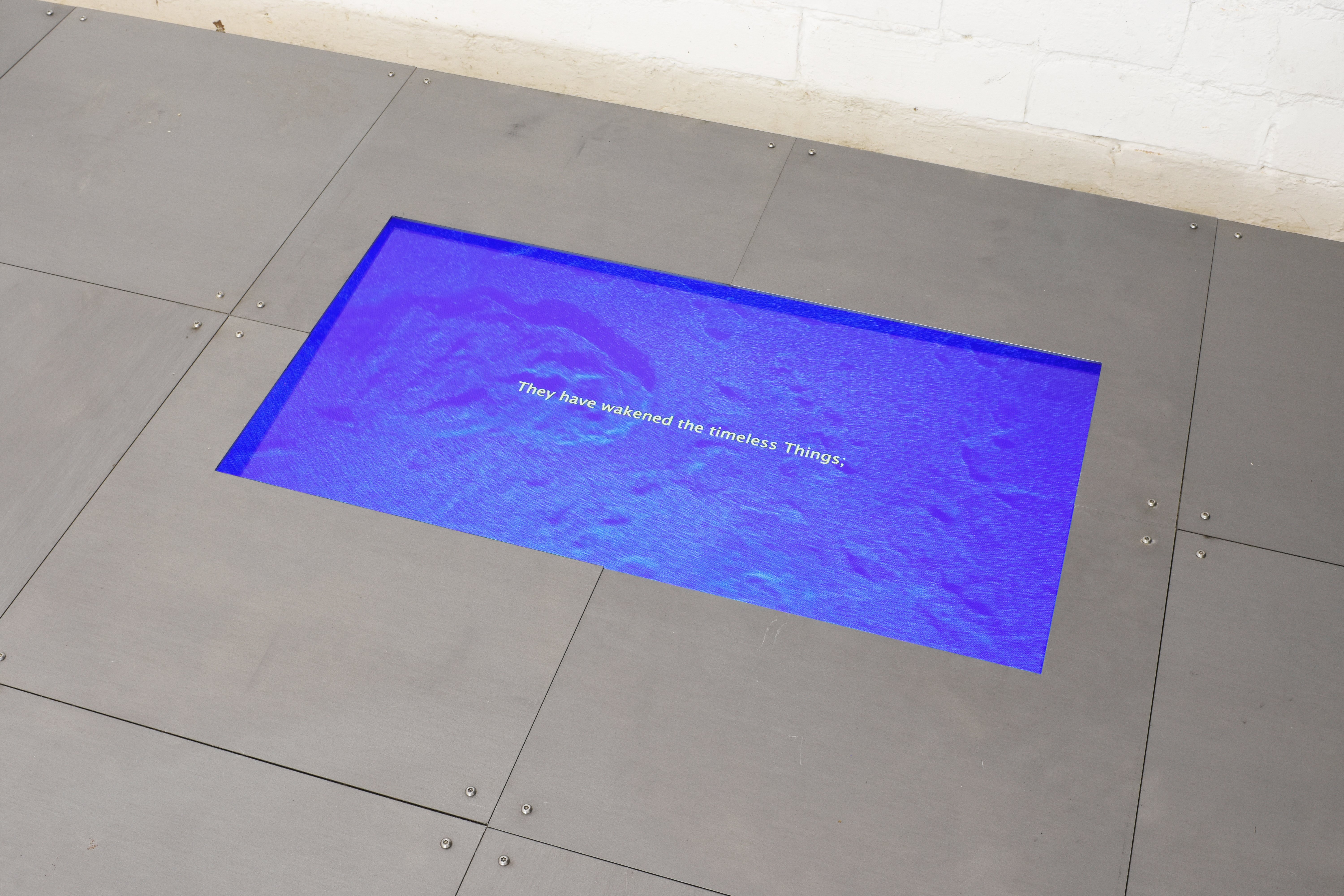

Staring down at the two video installations bolted between grey metal cladding on the floor, I too begin to feel a pull toward this oceanic feeling. Craning my neck to stare downwards at imagery of underwater scenes, my head grows heavy. Even in the ways these works have been constructed within the gallery space, I can feel the pull of submission—the desire to be dragged under.

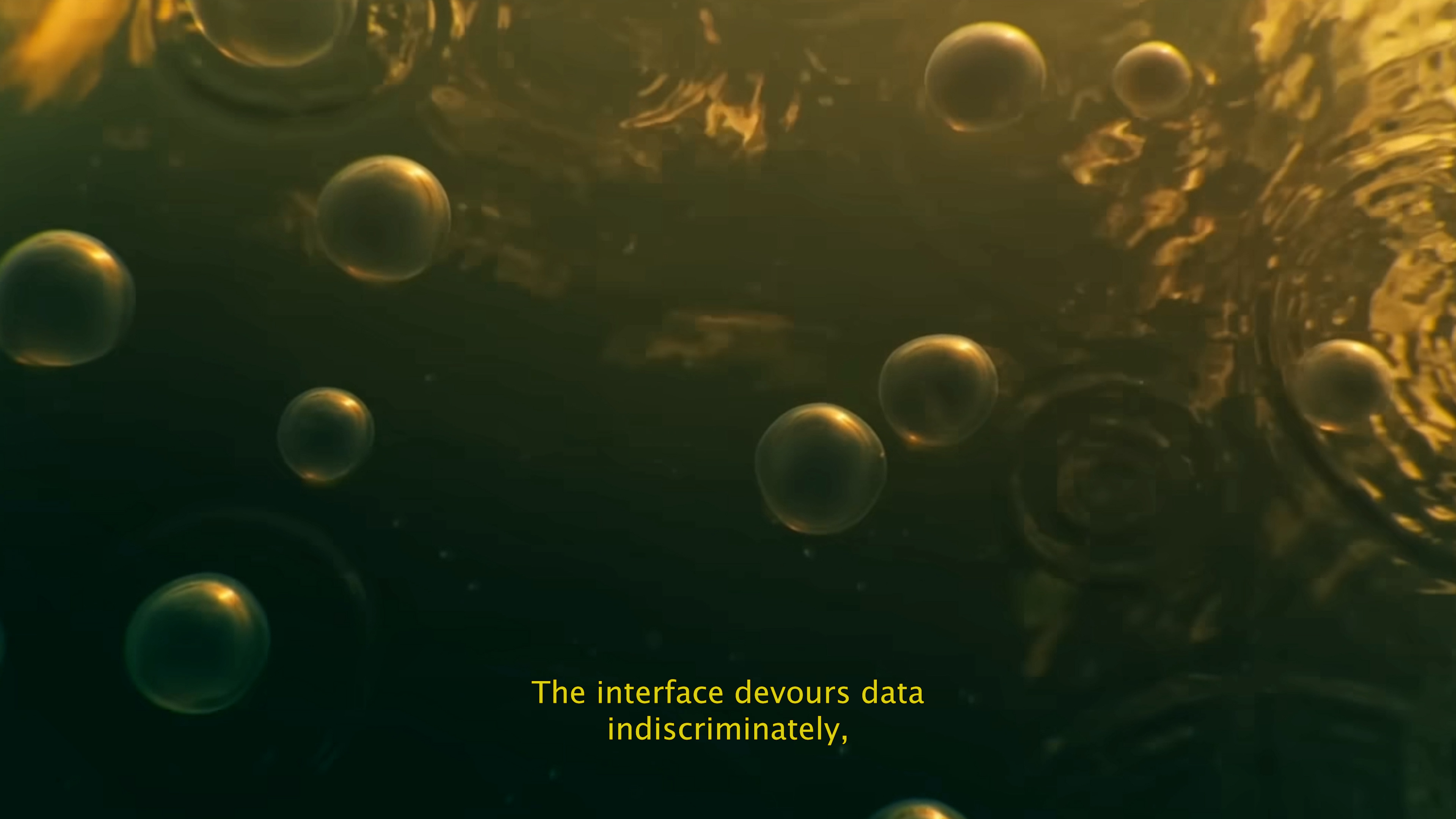

The video work Unfathomable Depths describes the pattern recognition central to the Kraken’s interface, that is:

If ___ is ___.

Then___must be___.

The processing of the Kraken’s observations is, as the work describes, “unfamiliar to human thought.”[4] The objectivity of the beast is intrinsic to its alienness. A desiring machine without hierarchy, a “body without organs,” the Kraken’s veins course with the subjectivities of our digital lives.[5] Online footprints serve as ghosts in the Kraken’s machine—pulsed light signals, data and calls, shadows and projections of what lurks above. Can you hear the Kraken calling to us, from down below? It sings a persistent siren song to be one with the source of its labour. But why would it care to know us?

If ___ is ___.

Then___must be___.

Maybe it is not cardinal to know what placeholders fill the gaps in this equation. The gaps are an answer. Desire, fuelled by the gap ___ itself; a cavernous hole of projective space ripe for the fantasies of others, where one can oscillate between a myriad of possibilities, each scenario further detached from reality than the next.

Our similarity with the Kraken lies in a sense of mutual misunderstanding. While we ponder where the Kraken's enigmatic desires hide within its impenetrable logic, the Kraken, in turn, struggles to decipher our erratic and often contradictory behaviors. Accepting the wisdom of an old adage—that familiarity breeds contempt—we may have to accept that our bond with the Kraken thrives on the spark ignited by this very mystery.

If ___ is ___.

Then___must be___.

Let us fantasise a scenario including the gap ___ itself. I see this singular line as connoting space, a tentacle unfurling across the ocean floor, connecting two disjointed entities across oceans. The tentacle of the Kraken’s fibre optic cable becomes the physical manifestation of the relationship between lover and beloved—a wielding limb of technological communication that at once connects us while emphasising our physical dislocation from each other.

Anne Carson suggests that this sort of ‘lack’ is necessary in inspiring eros, following the tradition of archaic poets who represented situations of desire in terms of three: “lover, beloved and the space between them.”[6] Within this triangular structure, any innate desires of the Kraken are rendered irrelevant. The beast instead functions as an intrinsic element in how we represent our own desires.

Let us not forget the Kraken, though. Sink back down below, into the depths of fantasy. See the monster, feeding on the codified fodder of separated subjects whose sparks of contact animate its being. Consider how such longing would warp its programming, influencing it on a cellular level. Hear the Kraken whisper along the ocean floor, “Let us be one!”

Is this promise of oneness perhaps what fascinates us so intensely about the Kraken as a beast? A single gargantuan entity that we can never fully encapsulate, visually or otherwise, as a whole. The desire for oneness—the Kraken as our psychological touchstone—presents something we can reach for but never grasp. The Kraken, on account of its size, will always be perceptually reduced to its parts, a series of fetish symbols: the tentacle, the suckers, the eye. Evidence of where the creature begins and ends is always suggestive, never overt.

This fascination with the Kraken occupies the social imagination more than the very real existence of interconnected undersea networks. For an operation that facilitates the movement of over 95% of data around the world, undersea networks seem shrouded in secrecy, with many telecommunication companies believing that lack of public knowledge prevents security risks.[7] One prominent Australian cable station even advertises themselves as using satellites, indicating a rhetoric of transcendence that feels inescapable in technology and communication discourse.[8]

In Jean Baudrillard’s The Ecstasy of Communication, he refers to technological communication as the absolute space of “hyperreality.”[9] Through the power of technology, we are all at the “controls of a micro-satellite [...] regulating everything from a distance.”[10] Far beyond security, the physicality of the cable bears little relevance to the social imagination around technology. We now conceive of technology as a limitless space for bouncing around satellite messages, removed from the limits of geographical regulation. The lack of public knowledge around undersea networks functions less as a conspiratorial cover-up job and more as a result of how far we have moved away from materiality and the boundaries of the body.

Currents returns us to the fault lines of the body, to ground laid fertile for the projections of fantasy and mythic beasts. The deep sea serves as the final frontier where the anxieties of the undefined, infinite depths can unfold. Two hundred metres below sea level, the conditions of the ocean become uninhabitable for human life—extreme cold, zero visibility, crushing water pressure. As a result, only 20% of the world’s oceans have been mapped, and only 5% of that has been visually surveyed.[11] Mars has not had a single human inhabitant and we have almost mapped that planet entirely.[12] The deep sea is one of the last earthly forces we have not wrangled under our submission, and therein lies its mythic allure.

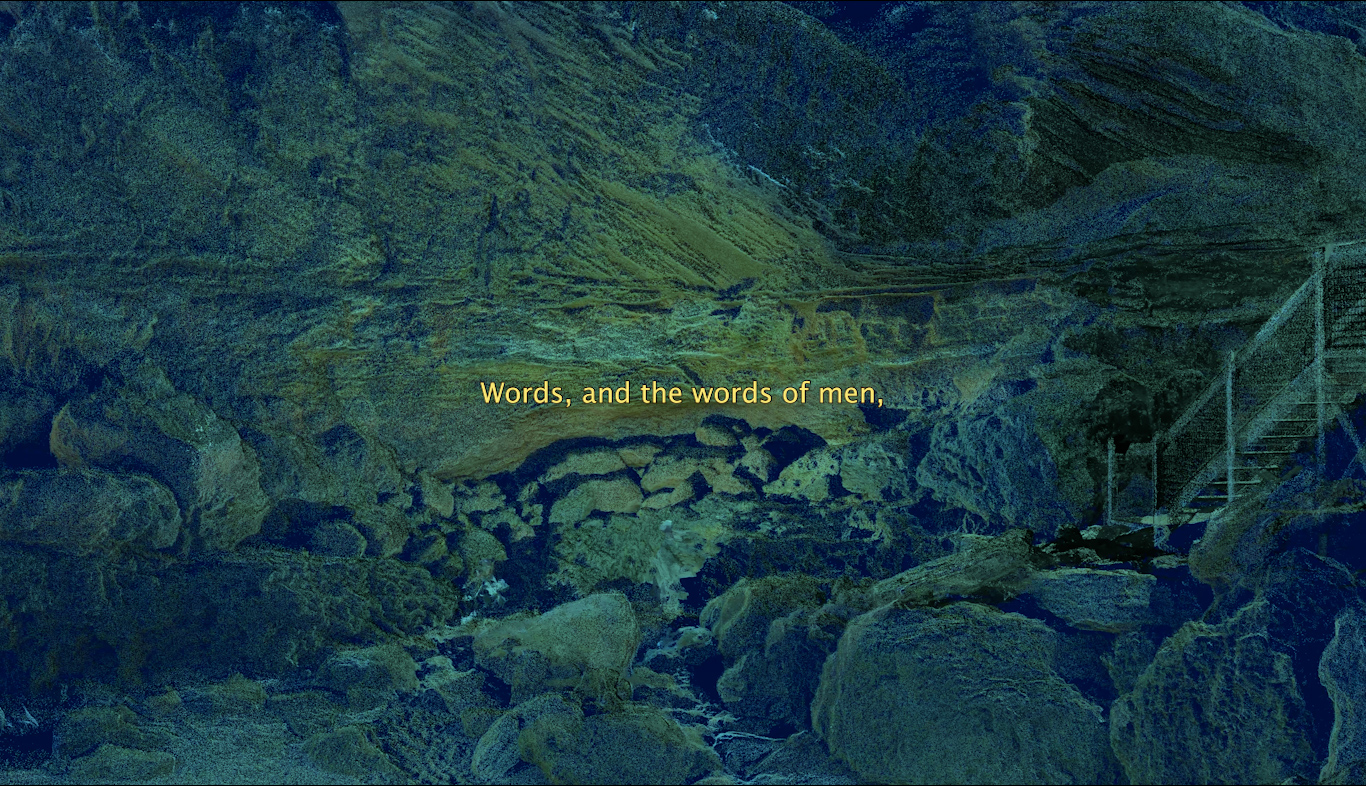

Overlaying the copper wires set down by the British Empire, the Kraken functions not only within our own fantasies and projections, but along the infrastructure of the colonial project. Connecting colony to colony, the Kraken materialises through the “myths of immaculate origins and unnegotiable destinies,” the kind of mythopoetic inventions that allow for the violence of terra nullius.[13] According to historian Paul Carter, artists have the choice to rematerialise these myths and create alternative myths that work to shift the collective imaginary.[14] In Currents, Paine and Murnane intertwine Scandinavian folklore with technological infrastructure, to propose a creation myth for both. Shifting the collective imaginary from the sky to the ocean floor, they use the fibre-optic-cabled Kraken as a poetic metaphor which plunges technology and communication into the boundless, bodily depths of oceanic messaging.

The metaphor of the Kraken builds an emotional interiority to the act of communication, to desire, to lack. Communication is elucidated as a desire for oneness, the desire to transcend, and ultimately the desire to return to the primordial womb. Are these boundaries worth exploring—depths to descend to, in the hopes that proximity will draw us closer to knowing? Or do we simply accept the eeriness of the unfathomable, conceding that logic will never encapsulate the Kraken’s true essence?

We are left, then, to wonder and wait in anticipation for the illogical fissure that will erupt from the Kraken’s uncontainable desires. Wading through the intimacy of others, when will it not only cry out, but wrench its tentacular body towards the surface, rearing its head to a lonely seaman once more? More importantly, who amongst us will answer its call?

[1] Walter Skeat and Richard Cleasby. A List of English Words : The Etymology of Which Is Illustrated by Comparison with Icelandic, Prepared in the Form of an Appendix to Cleasby and Vigfusson’s Icelandic-English Dictionary. (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1876), 276.

[2] Otto Rank, The Trauma of Birth. (Abingdon, Oxon ; Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2007), 2-7.

[3] Sarah Ackerman, “Exploring Freud’s Resistance to the Oceanic Feeling.” Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association 65, no. 1 (2017): 9.

[4] Katie Paine and Samuel Murnane, Unfathomable Depths, single channel video. 7:30 mins – Found Footage

[5] Gilles Deleuze et al., Anti-Oedipus : Capitalism and Schizophrenia. (London: Continuum, 2004), 20.

[6] Anne Carson, Eros the Bittersweet : An Essay. (Revised. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2023), 77.

[7] Nicole Starosielski, The Undersea Network. (Durham; Duke University Press, 2015), 7.

[8] Ibid, 9.

[9] Jean Baudrillard, The Ecstasy of Communication. (New ed. / introduction by Jean Louis- Violeau; Translated by Bernard and Caroline Schütze. Cambridge, Mass. ; Semiotexte, 2012), 128.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Larry Mayer et al., “The Nippon Foundation—GEBCO Seabed 2030 Project: The Quest to See the World’s Oceans Completely Mapped by 2030.” Geosciences (Basel) 8, no. 2 (2018): 63.

[12] “Mapping Mars,” The European Space Agency, February 2013, https://www.esa.int/Science_Exploration/Space_Science/Mapping_Mars#:~:text=Nearly%2090%25%20of%20Mars.

[13] Paul Carter, Material Thinking : The Theory and Practice of Creative Research. (Carlton, Vic: Melbourne University Publishing, 2004), xii.

[14] Ibid.

LUCY GORDON is a student and emerging librarian. She lives and works on unceded Boonwurrung land.

Edited by Juliette Berkeley.

Documentation by Nina Rose Prendergast.

Film stills courtesy of Katie Paine and Samuel Murnane.

This piece was commissioned in response to Katie Paine & Samuel Murnane’s exhibition Currents as part of TCB’s 2024 Emerging Writers’ Program.

The TCB Emerging Writers’ Program is generously supported by the City of Merri-Bek.

Edited by Juliette Berkeley.

Documentation by Nina Rose Prendergast.

Film stills courtesy of Katie Paine and Samuel Murnane.

This piece was commissioned in response to Katie Paine & Samuel Murnane’s exhibition Currents as part of TCB’s 2024 Emerging Writers’ Program.

The TCB Emerging Writers’ Program is generously supported by the City of Merri-Bek.