VIRGINIA OVERELL

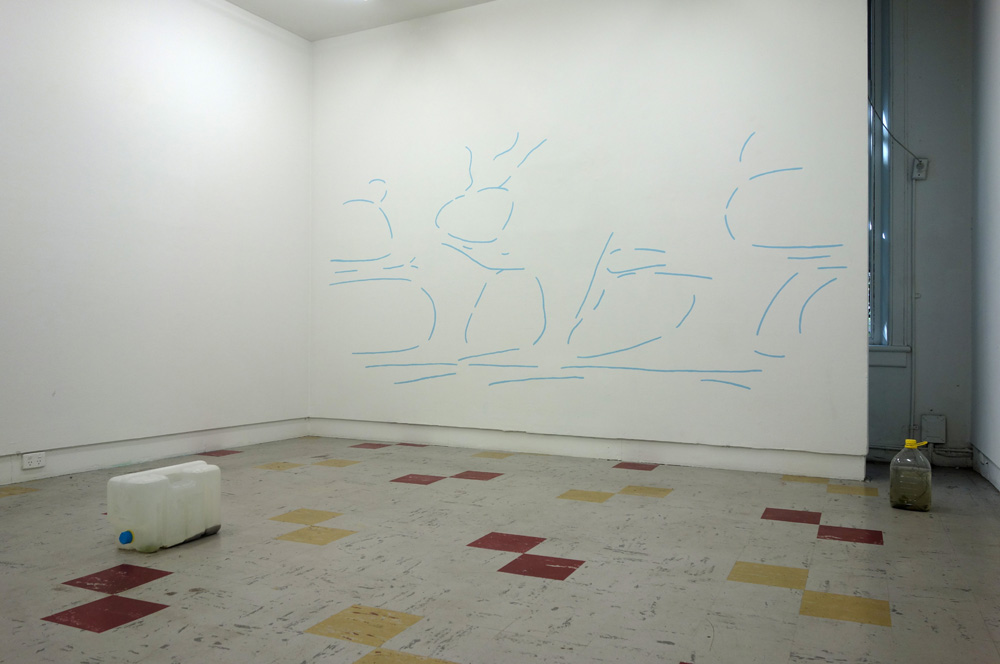

Embankment

16 Apr 2014—03 May 2014

Embankment is concerned with ways of thinking about the sea.

Water maybe from the Southern Ocean, the Pacific Ocean or the Indian Ocean via the Tasman Sea comes into Bass Strait then into Port Phillip Bay. Two 15 litre bottles are filled at Edithvale Beach and moved inland to China Town.

Virginia Overell completed a Bachelor of Fine Arts (Honours) at the Victorian College of the Arts in 2012. She has participated in exhibitions at Gertrude Contemporary, Conical Inc, Margaret Lawrence Gallery, Slopes and TCB. She has been a recipient of the Australia Council Artstart Grant and has undertaken a residency as part of the Studio program at the National Gallery of Victoria, Australia.

This project has been assisted by the Australian Government through the Australia Council for the Arts, its arts funding and advisory body.

it is human

nature to stand

in the middle

of a thing,

but you cannot

stand in the middle

of this; 1

How do we think about the ocean, when we think about the ocean?

I can only conceive of it in small parts. The oceans combined; the world ocean, how can it be imagined

outside of the flat, blue, static ocean of maps? One of the more pervasive sea visions is that of its vastness

It is “as close an approximation of the infinite as the visible and physical world can provide.”2 Imagine yourself as a body in open water. Orientation is limited to being on (above) the water or in (below). Are you on or in the water? The boundless ocean.

The Australian continent is surrounded by water on all sides. We are isolated by the enormity of the oceans between us and other countries, but the ocean doesn’t just sit between countries, it connects them. Oceanic trade routes developed along side colonisation through the interpretation and mapping of the planetary currents. A circular system of trade began across the Atlantic connecting Europe, Africa and the Americas in the late sixteenth century. The ocean continues to be a site of exchange. Enormous container ships transport commodity and capital. “The conduct of life today is completely and utterly dependent on the seas and the ships it bears, yet nothing is more invisible.”3 This invisibility is echoed within the transport of human bodies through these waters via the ‘export’ of asylum seekers.

We have drawn lines on the sea to map currents and trade routes, to show latitude, longitude, rhumb and bathymetric lines, and 0more recent lines define territorial waters, contiguous zones, exclusive economic zones and the High Seas. Experiences of the ocean have been constructed and meditated through these lines drawn on its surface. Some of the lines are intended to enclose spaces and commodify 0its resources (gas, oil, fishing rights). But the ocean is a “space characterised by movement”4 and these borderlines are chimerical. Where does the water of Port Phillip Bay become the water of the Bass Strait, or the Tasman Sea, or the Pacific Ocean? Do rivers begin or end at the ocean?

We are limited in our ability to transform the sea by drawing lines on it, as the processes of colonisation so seamlessly did in their transformation of foreign lands. These lines in part allow us to approach the difficult task of conceptualising the ocean as a whole. “The partial nature of our encounter with the ocean necessarily creates gaps, as the unrepresentable becomes the unacknowledged, and then the unacknowledged becomes the unthinkable.”5

________________

1 Marianne Moore, “A Grave.” Complete Poems, (New York: Penguin,1994), 49.

2 Christopher Connery, “There was No More Sea.” Journal of Historical Geography 32 (2006): 508.

3 Michael Taussig, “The Beach (A Fantasy).” Landscape and Power, (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994), 318.

4 Philip E. Steinberg, “Of Other Seas,” Atlantic Studies 10:2 (2013): 156.

5 Steinberg, “Of Other Seas,” 157.